Decoration Day at Arlington, 1871

As many readers will know, the practice of setting aside a specific day to honor fallen soldiers sprung up spontaneously across the country, North and South, in the years following the Civil War. One of the earliest — perhaps the earliest — of these events was the ceremony held on May 1, 1865 in newly-occupied Charleston, South Carolina, by that community’s African American population, honoring the Union prisoners buried at the site of the city’s old fairgrounds and racecourse, as described in David Blight’s Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory.

Over the years, “Decoration Day” events gradually coalesced around late May, particularly after 1868, when General John A. Logan, commander-in-chief of the Grand Army of the Republic, called for a day of remembrance on May 30 of that year. It was a date chosen specifically not to coincide with the anniversary of any major action of the war, to be an occasion in its own right. While Memorial Day is now observed nationwide, parallel observances throughout the South honor the Confederate dead, and still hold official or semi-official recognition by the former states of the Confederacy.

Recently while researching the life of a particular Union soldier, I came across a story from a black newspaper, the New Orleans Semi-Weekly Louisianan dated June 15, 1871. It describes an event that occurred at the then-newly-established Arlington National Cemetery. Like the U.S. Colored Troops who’d been denied a place in the grand victory parade in Washington in May 1865, the black veterans discovered that segregation and exclusion within the military continued even after death:

DECORATION DAY AND HYPOCRISY.

The custom of decorating the graves of soldiers who fell in the late war, seems to be doing more harm to the living than it does to honor the dead. In every Southern State there are not only separate localities where the respective defendants of Unionism and Secession lie buried, but there are different days of observance, a rivalry in the ostentatious parade for floral wealth and variety, and a competition in extravagant eulogy, more calculated to inflame the passions than to soften and purify the affections, which ought to be the result of all funeral rights.

Besides this bad effect among the whites there comes a still more evil influence from the dastardly discriminations made by the professedly union [sic.] people themselves.

Read this extract from the Washington Chronicle:

AT THE COLORED CEMETERY

While services were in progress at the tomb of the “Unknown” Comrade Charles Guthridge, John S. Brent, and Beverly Tucker, of Thomas R. Hawkins Post, No. 14 G.A.R., followed by Greene’s Brass Band, Colonel Perry Carson’s Pioneer Corps of the 17th District, Butler Zouaves, under the command of Charles B. Fisher, and a large number of colored persons proceeded to the cemetery on the colored soldiers to the north of the mansion, and on arriving there they found no stand erected, no orator or speaker selected, not a single flag placed on high, not even a paper flag at the head boards of these loyal but ignored dead, not even a drop of water to quench the thirst of the humble patriots after their toilsome march from the beautifully decorated grand stand above to this barren neglected spot below. At 2 ½ o’clock P.M., no flowers or other articles coming for decorative purposes, messengers were dispatched to the officers of the day for them; they in time returned with a half dozen (perhaps more) rosettes, and a basket of flower leaves. Deep was the indignation and disappointment of the people. A volley of musketry was fired over the graves by Col. Fisher’s company. An indignation meeting was improvised, Col. Fisher acting president. A short but eloquent address was made by George Hatton, who was followed by F. G. Barbadoes, who concluded his remarks by offering the followign resolutions, which were unanimously adopted:

Resolved, that the colored citizens of the District of Columbia hereby respectfully request the proper authorities to remove the remains of all loyal soldiers now interred at the north end of the Arlington cemetery, among paupers and rebels, to the main body of the grounds at the earliest possible moment.

Resolved, that the following named gentlemen are hereby created a committee to proffer our request and to take such further action in the matter as may be deemed necessary to a successful accomplishment of our wishes: Frederick Douglass, John M. Langston, Rev. Dr. Anderson, William J. Wilson, Col. Charles B. Fisher, William Wormley, Perry Carson, Dr. A. T. Augusta, F. G. Barbadoes.

If any event in the whole history of our connection with the late war embodied more features of disgraceful neglect, or exhibited more clearly the necessity of protecting ourselves from insult, than this behavior at Arlington heights, we at least acknowledge ignorance of it.

We say again that no good, but only harm can result from keeping up the recollection of the bitter strife and bloodshed between North and South, and worse still, in furnishing occasion to white Unionists of proving their hypocrisy towards the negro in the very presence of our dead.

The black soldiers’ graves were never moved; rather, the boundaries of Arlington were gradually expanded to encompass them, in what is now known as Section 27. Most of the graves, originally marked with simple wooden boards, were subsequently marked with proper headstones, though many are listed as “unknown.” In addition to the black Union soldiers interred there, roughly 3,800 civilians, mostly freedmen, lie there as well, many under stones with the simple, but profoundly important, designation of “citizen.” The remains of Confederate prisoners buried there were removed in the early 1900s to a new plot on the western edge of the cemetery complex, where the Confederate Monument would be dedicated in 1914.

The black soldiers’ graves were never moved; rather, the boundaries of Arlington were gradually expanded to encompass them, in what is now known as Section 27. Most of the graves, originally marked with simple wooden boards, were subsequently marked with proper headstones, though many are listed as “unknown.” In addition to the black Union soldiers interred there, roughly 3,800 civilians, mostly freedmen, lie there as well, many under stones with the simple, but profoundly important, designation of “citizen.” The remains of Confederate prisoners buried there were removed in the early 1900s to a new plot on the western edge of the cemetery complex, where the Confederate Monument would be dedicated in 1914.

Unfortunately, the more things change, the more. . . well, you know. In part because that segment of the cemetery began as a burial ground for blacks, prisoners and others of lesser status, the records for Section 27 are fragmentary. Further, Section 27 has — whether by design or happenstance — suffered an alarming amount of negligence and lack of attention over the years. The Army has promised, and continues to promise, that these problems will be corrected.

As Americans, North and South, we should all expect nothing less.

____________________________________

Images of Section 27, Arlington National Cemetery, © Scott Holter, all rights reserved. Used with permission. Thanks to Coatesian commenter KewHall (no relation) for the research tip.

Decoration Day at Arlington, 1871

As many readers will know, the practice of setting aside a specific day to honor fallen soldiers sprung up spontaneously across the country, North and South, in the years following the Civil War. One of the earliest — perhaps the earliest — of these events was the ceremony held on May 1, 1865 in newly-occupied Charleston, South Carolina, by that community’s African American population, honoring the Union prisoners buried at the site of the city’s old fairgrounds and racecourse, as described in David Blight’s Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory.

Over the years, “Decoration Day” events gradually coalesced around late May, particularly after 1868, when General John A. Logan, commander-in-chief of the Grand Army of the Republic, called for a day of remembrance on May 30 of that year. It was a date chosen specifically not to coincide with the anniversary of any major action of the war, to be an occasion in its own right. While Memorial Day is now observed nationwide, parallel observances throughout the South honor the Confederate dead, and still hold official or semi-official recognition by the former states of the Confederacy.

Recently while researching the life of a particular Union soldier, I came across a story from a black newspaper, the New Orleans Semi-Weekly Louisianan dated June 15, 1871. It describes an event that occurred at the then-newly-established Arlington National Cemetery. Like the U.S. Colored Troops who’d been denied a place in the grand victory parade in Washington in May 1865, the black veterans discovered that segregation and exclusion within the military continued even after death:

DECORATION DAY AND HYPOCRISY.

The custom of decorating the graves of soldiers who fell in the late war, seems to be doing more harm to the living than it does to honor the dead. In every Southern State there are not only separate localities where the respective defendants of Unionism and Secession lie buried, but there are different days of observance, a rivalry in the ostentatious parade for floral wealth and variety, and a competition in extravagant eulogy, more calculated to inflame the passions than to soften and purify the affections, which ought to be the result of all funeral rights.

Besides this bad effect among the whites there comes a still more evil influence from the dastardly discriminations made by the professedly union [sic.] people themselves.

Read this extract from the Washington Chronicle:

AT THE COLORED CEMETERY

While services were in progress at the tomb of the “Unknown” Comrade Charles Guthridge, John S. Brent, and Beverly Tucker, of Thomas R. Hawkins Post, No. 14 G.A.R., followed by Greene’s Brass Band, Colonel Perry Carson’s Pioneer Corps of the 17th District, Butler Zouaves, under the command of Charles B. Fisher, and a large number of colored persons proceeded to the cemetery on the colored soldiers to the north of the mansion, and on arriving there they found no stand erected, no orator or speaker selected, not a single flag placed on high, not even a paper flag at the head boards of these loyal but ignored dead, not even a drop of water to quench the thirst of the humble patriots after their toilsome march from the beautifully decorated grand stand above to this barren neglected spot below. At 2 ½ o’clock P.M., no flowers or other articles coming for decorative purposes, messengers were dispatched to the officers of the day for them; they in time returned with a half dozen (perhaps more) rosettes, and a basket of flower leaves. Deep was the indignation and disappointment of the people. A volley of musketry was fired over the graves by Col. Fisher’s company. An indignation meeting was improvised, Col. Fisher acting president. A short but eloquent address was made by George Hatton, who was followed by F. G. Barbadoes, who concluded his remarks by offering the followign resolutions, which were unanimously adopted:

Resolved, that the colored citizens of the District of Columbia hereby respectfully request the proper authorities to remove the remains of all loyal soldiers now interred at the north end of the Arlington cemetery, among paupers and rebels, to the main body of the grounds at the earliest possible moment.

Resolved, that the following named gentlemen are hereby created a committee to proffer our request and to take such further action in the matter as may be deemed necessary to a successful accomplishment of our wishes: Frederick Douglass, John M. Langston, Rev. Dr. Anderson, William J. Wilson, Col. Charles B. Fisher, William Wormley, Perry Carson, Dr. A. T. Augusta, F. G. Barbadoes.

If any event in the whole history of our connection with the late war embodied more features of disgraceful neglect, or exhibited more clearly the necessity of protecting ourselves from insult, than this behavior at Arlington heights, we at least acknowledge ignorance of it.

We say again that no good, but only harm can result from keeping up the recollection of the bitter strife and bloodshed between North and South, and worse still, in furnishing occasion to white Unionists of proving their hypocrisy towards the negro in the very presence of our dead.

The black soldiers’ graves were never moved; rather, the boundaries of Arlington were gradually expanded to encompass them, in what is now known as Section 27. Most of the graves, originally marked with simple wooden boards, were subsequently marked with proper headstones, though many are listed as “unknown.” In addition to the black Union soldiers interred there, roughly 3,800 civilians, mostly freedmen, lie there as well, many under stones with the simple, but profoundly important, designation of “citizen.” The remains of Confederate prisoners buried there were removed in the early 1900s to a new plot on the western edge of the cemetery complex, where the Confederate Monument would be dedicated in 1914.

The black soldiers’ graves were never moved; rather, the boundaries of Arlington were gradually expanded to encompass them, in what is now known as Section 27. Most of the graves, originally marked with simple wooden boards, were subsequently marked with proper headstones, though many are listed as “unknown.” In addition to the black Union soldiers interred there, roughly 3,800 civilians, mostly freedmen, lie there as well, many under stones with the simple, but profoundly important, designation of “citizen.” The remains of Confederate prisoners buried there were removed in the early 1900s to a new plot on the western edge of the cemetery complex, where the Confederate Monument would be dedicated in 1914.

Unfortunately, the more things change, the more. . . well, you know. In part because that segment of the cemetery began as a burial ground for blacks, prisoners and others of lesser status, the records for Section 27 are fragmentary. Further, Section 27 has — whether by design or happenstance — suffered an alarming amount of negligence and lack of attention over the years. The Army has promised, and continues to promise, that these problems will be corrected.

As Americans, North and South, we should all expect nothing less.

____________________________________

Images of Section 27, Arlington National Cemetery, © Scott Holter, all rights reserved. Used with permission. Thanks to Coatesian commenter KewHall (no relation) for the research tip.

Decoration Day at Arlington, 1871

As many readers will know, the practice of setting aside a specific day to honor fallen soldiers sprung up spontaneously across the country, North and South, in the years following the Civil War. One of the earliest — perhaps the earliest — of these events was the ceremony held on May 1, 1865 in newly-occupied Charleston, South Carolina, by that community’s African American population, honoring the Union prisoners buried at the site of the city’s old fairgrounds and racecourse, as described in David Blight’s Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory.

Over the years, “Decoration Day” events gradually coalesced around late May, particularly after 1868, when General John A. Logan, commander-in-chief of the Grand Army of the Republic, called for a day of remembrance on May 30 of that year. It was a date chosen specifically not to coincide with the anniversary of any major action of the war, to be an occasion in its own right. While Memorial Day is now observed nationwide, parallel observances throughout the South honor the Confederate dead, and still hold official or semi-official recognition by the former states of the Confederacy.

Recently while researching the life of a particular Union soldier, I came across a story from a black newspaper, the New Orleans Semi-Weekly Louisianan dated June 15, 1871. It describes an event that occurred at the then-newly-established Arlington National Cemetery. Like the U.S. Colored Troops who’d been denied a place in the grand victory parade in Washington in May 1865, the black veterans discovered that segregation and exclusion within the military continued even after death:

DECORATION DAY AND HYPOCRISY.

The custom of decorating the graves of soldiers who fell in the late war, seems to be doing more harm to the living than it does to honor the dead. In every Southern State there are not only separate localities where the respective defendants of Unionism and Secession lie buried, but there are different days of observance, a rivalry in the ostentatious parade for floral wealth and variety, and a competition in extravagant eulogy, more calculated to inflame the passions than to soften and purify the affections, which ought to be the result of all funeral rights.

Besides this bad effect among the whites there comes a still more evil influence from the dastardly discriminations made by the professedly union [sic.] people themselves.

Read this extract from the Washington Chronicle:

AT THE COLORED CEMETERY

While services were in progress at the tomb of the “Unknown” Comrade Charles Guthridge, John S. Brent, and Beverly Tucker, of Thomas R. Hawkins Post, No. 14 G.A.R., followed by Greene’s Brass Band, Colonel Perry Carson’s Pioneer Corps of the 17th District, Butler Zouaves, under the command of Charles B. Fisher, and a large number of colored persons proceeded to the cemetery on the colored soldiers to the north of the mansion, and on arriving there they found no stand erected, no orator or speaker selected, not a single flag placed on high, not even a paper flag at the head boards of these loyal but ignored dead, not even a drop of water to quench the thirst of the humble patriots after their toilsome march from the beautifully decorated grand stand above to this barren neglected spot below. At 2 ½ o’clock P.M., no flowers or other articles coming for decorative purposes, messengers were dispatched to the officers of the day for them; they in time returned with a half dozen (perhaps more) rosettes, and a basket of flower leaves. Deep was the indignation and disappointment of the people. A volley of musketry was fired over the graves by Col. Fisher’s company. An indignation meeting was improvised, Col. Fisher acting president. A short but eloquent address was made by George Hatton, who was followed by F. G. Barbadoes, who concluded his remarks by offering the followign resolutions, which were unanimously adopted:

Resolved, that the colored citizens of the District of Columbia hereby respectfully request the proper authorities to remove the remains of all loyal soldiers now interred at the north end of the Arlington cemetery, among paupers and rebels, to the main body of the grounds at the earliest possible moment.

Resolved, that the following named gentlemen are hereby created a committee to proffer our request and to take such further action in the matter as may be deemed necessary to a successful accomplishment of our wishes: Frederick Douglass, John M. Langston, Rev. Dr. Anderson, William J. Wilson, Col. Charles B. Fisher, William Wormley, Perry Carson, Dr. A. T. Augusta, F. G. Barbadoes.

If any event in the whole history of our connection with the late war embodied more features of disgraceful neglect, or exhibited more clearly the necessity of protecting ourselves from insult, than this behavior at Arlington heights, we at least acknowledge ignorance of it.

We say again that no good, but only harm can result from keeping up the recollection of the bitter strife and bloodshed between North and South, and worse still, in furnishing occasion to white Unionists of proving their hypocrisy towards the negro in the very presence of our dead.

The black soldiers’ graves were never moved; rather, the boundaries of Arlington were gradually expanded to encompass them, in what is now known as Section 27. Most of the graves, originally marked with simple wooden boards, were subsequently marked with proper headstones, though many are listed as “unknown.” In addition to the black Union soldiers interred there, roughly 3,800 civilians, mostly freedmen, lie there as well, many under stones with the simple, but profoundly important, designation of “citizen.” The remains of Confederate prisoners buried there were removed in the early 1900s to a new plot on the western edge of the cemetery complex, where the Confederate Monument would be dedicated in 1914.

The black soldiers’ graves were never moved; rather, the boundaries of Arlington were gradually expanded to encompass them, in what is now known as Section 27. Most of the graves, originally marked with simple wooden boards, were subsequently marked with proper headstones, though many are listed as “unknown.” In addition to the black Union soldiers interred there, roughly 3,800 civilians, mostly freedmen, lie there as well, many under stones with the simple, but profoundly important, designation of “citizen.” The remains of Confederate prisoners buried there were removed in the early 1900s to a new plot on the western edge of the cemetery complex, where the Confederate Monument would be dedicated in 1914.

Unfortunately, the more things change, the more. . . well, you know. In part because that segment of the cemetery began as a burial ground for blacks, prisoners and others of lesser status, the records for Section 27 are fragmentary. Further, Section 27 has — whether by design or happenstance — suffered an alarming amount of negligence and lack of attention over the years. The Army has promised, and continues to promise, that these problems will be corrected.

As Americans, North and South, we should all expect nothing less.

____________________________________

Images of Section 27, Arlington National Cemetery, © Scott Holter, all rights reserved. Used with permission. Thanks to Coatesian commenter KewHall (no relation) for the research tip.

Decoration Day at Arlington, 1871

As many readers will know, the practice of setting aside a specific day to honor fallen soldiers sprung up spontaneously across the country, North and South, in the years following the Civil War. One of the earliest — perhaps the earliest — of these events was the ceremony held on May 1, 1865 in newly-occupied Charleston, South Carolina, by that community’s African American population, honoring the Union prisoners buried at the site of the city’s old fairgrounds and racecourse, as described in David Blight’s Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory.

Over the years, “Decoration Day” events gradually coalesced around late May, particularly after 1868, when General John A. Logan, commander-in-chief of the Grand Army of the Republic, called for a day of remembrance on May 30 of that year. It was a date chosen specifically not to coincide with the anniversary of any major action of the war, to be an occasion in its own right. While Memorial Day is now observed nationwide, parallel observances throughout the South honor the Confederate dead, and still hold official or semi-official recognition by the former states of the Confederacy.

Recently while researching the life of a particular Union soldier, I came across a story from a black newspaper, the New Orleans Semi-Weekly Louisianan dated June 15, 1871. It describes an event that occurred at the then-newly-established Arlington National Cemetery. Like the U.S. Colored Troops who’d been denied a place in the grand victory parade in Washington in May 1865, the black veterans discovered that segregation and exclusion within the military continued even after death:

DECORATION DAY AND HYPOCRISY.

The custom of decorating the graves of soldiers who fell in the late war, seems to be doing more harm to the living than it does to honor the dead. In every Southern State there are not only separate localities where the respective defendants of Unionism and Secession lie buried, but there are different days of observance, a rivalry in the ostentatious parade for floral wealth and variety, and a competition in extravagant eulogy, more calculated to inflame the passions than to soften and purify the affections, which ought to be the result of all funeral rights.

Besides this bad effect among the whites there comes a still more evil influence from the dastardly discriminations made by the professedly union [sic.] people themselves.

Read this extract from the Washington Chronicle:

AT THE COLORED CEMETERY

While services were in progress at the tomb of the “Unknown” Comrade Charles Guthridge, John S. Brent, and Beverly Tucker, of Thomas R. Hawkins Post, No. 14 G.A.R., followed by Greene’s Brass Band, Colonel Perry Carson’s Pioneer Corps of the 17th District, Butler Zouaves, under the command of Charles B. Fisher, and a large number of colored persons proceeded to the cemetery on the colored soldiers to the north of the mansion, and on arriving there they found no stand erected, no orator or speaker selected, not a single flag placed on high, not even a paper flag at the head boards of these loyal but ignored dead, not even a drop of water to quench the thirst of the humble patriots after their toilsome march from the beautifully decorated grand stand above to this barren neglected spot below. At 2 ½ o’clock P.M., no flowers or other articles coming for decorative purposes, messengers were dispatched to the officers of the day for them; they in time returned with a half dozen (perhaps more) rosettes, and a basket of flower leaves. Deep was the indignation and disappointment of the people. A volley of musketry was fired over the graves by Col. Fisher’s company. An indignation meeting was improvised, Col. Fisher acting president. A short but eloquent address was made by George Hatton, who was followed by F. G. Barbadoes, who concluded his remarks by offering the followign resolutions, which were unanimously adopted:

Resolved, that the colored citizens of the District of Columbia hereby respectfully request the proper authorities to remove the remains of all loyal soldiers now interred at the north end of the Arlington cemetery, among paupers and rebels, to the main body of the grounds at the earliest possible moment.

Resolved, that the following named gentlemen are hereby created a committee to proffer our request and to take such further action in the matter as may be deemed necessary to a successful accomplishment of our wishes: Frederick Douglass, John M. Langston, Rev. Dr. Anderson, William J. Wilson, Col. Charles B. Fisher, William Wormley, Perry Carson, Dr. A. T. Augusta, F. G. Barbadoes.

If any event in the whole history of our connection with the late war embodied more features of disgraceful neglect, or exhibited more clearly the necessity of protecting ourselves from insult, than this behavior at Arlington heights, we at least acknowledge ignorance of it.

We say again that no good, but only harm can result from keeping up the recollection of the bitter strife and bloodshed between North and South, and worse still, in furnishing occasion to white Unionists of proving their hypocrisy towards the negro in the very presence of our dead.

The black soldiers’ graves were never moved; rather, the boundaries of Arlington were gradually expanded to encompass them, in what is now known as Section 27. Most of the graves, originally marked with simple wooden boards, were subsequently marked with proper headstones, though many are listed as “unknown.” In addition to the black Union soldiers interred there, roughly 3,800 civilians, mostly freedmen, lie there as well, many under stones with the simple, but profoundly important, designation of “citizen.” The remains of Confederate prisoners buried there were removed in the early 1900s to a new plot on the western edge of the cemetery complex, where the Confederate Monument would be dedicated in 1914.

The black soldiers’ graves were never moved; rather, the boundaries of Arlington were gradually expanded to encompass them, in what is now known as Section 27. Most of the graves, originally marked with simple wooden boards, were subsequently marked with proper headstones, though many are listed as “unknown.” In addition to the black Union soldiers interred there, roughly 3,800 civilians, mostly freedmen, lie there as well, many under stones with the simple, but profoundly important, designation of “citizen.” The remains of Confederate prisoners buried there were removed in the early 1900s to a new plot on the western edge of the cemetery complex, where the Confederate Monument would be dedicated in 1914.

Unfortunately, the more things change, the more. . . well, you know. In part because that segment of the cemetery began as a burial ground for blacks, prisoners and others of lesser status, the records for Section 27 are fragmentary. Further, Section 27 has — whether by design or happenstance — suffered an alarming amount of negligence and lack of attention over the years. The Army has promised, and continues to promise, that these problems will be corrected.

As Americans, North and South, we should all expect nothing less.

____________________________________

Images of Section 27, Arlington National Cemetery, © Scott Holter, all rights reserved. Used with permission. Thanks to Coatesian commenter KewHall (no relation) for the research tip.

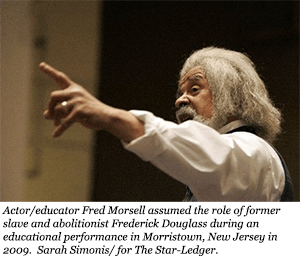

Frederick Douglass’ Black Confederate

A few weeks ago Harvard historian John Stauffer published an essay in The Root entitled, “Yes, There Were Black Confederates. Here’s Why.” Stauffer’s essay was largely an expansion of a talk he gave in 2011, which itself reflected little more research than Googling around the web for well-worn anecdotes. Stauffer’s Root piece was mostly panned by historians who have closely studied the “black Confederate” theme, particularly by my blogging colleagues Kevin Levin and Brooks Simpson. Both continued that discussion through follow-up posts. I wrote about it as well, pointing out that Stauffer identified one of Frederick Douglass’ sources in 1861 as an African American man who claimed to have seen “one regiment [at Manassas] of 700 black men from Georgia, 1000 [men] from South Carolina, and about 1000 [men with him from] Virginia, destined for Manassas when he ran away.” Unfortunately Stauffer appears not to have followed up on the source of that quote, which actually appeared in the Boston Daily Journal and Evening Transcript newspapers in February 1862, roughly six months after Douglass wrote about them in his newsletter.

A few weeks ago Harvard historian John Stauffer published an essay in The Root entitled, “Yes, There Were Black Confederates. Here’s Why.” Stauffer’s essay was largely an expansion of a talk he gave in 2011, which itself reflected little more research than Googling around the web for well-worn anecdotes. Stauffer’s Root piece was mostly panned by historians who have closely studied the “black Confederate” theme, particularly by my blogging colleagues Kevin Levin and Brooks Simpson. Both continued that discussion through follow-up posts. I wrote about it as well, pointing out that Stauffer identified one of Frederick Douglass’ sources in 1861 as an African American man who claimed to have seen “one regiment [at Manassas] of 700 black men from Georgia, 1000 [men] from South Carolina, and about 1000 [men with him from] Virginia, destined for Manassas when he ran away.” Unfortunately Stauffer appears not to have followed up on the source of that quote, which actually appeared in the Boston Daily Journal and Evening Transcript newspapers in February 1862, roughly six months after Douglass wrote about them in his newsletter.

Douglass was making the rounds as a speaker that winter, and the man Stauffer cited as Douglass’ source had appeared with him at an Emancipation League at the Tremont Temple on February 5, 1862. That address must have given Douglass great satisfaction, as just fourteen months previously Douglass and other abolitionists had been forcibly ejected from that same venue on orders of Boston’s mayor.

But, as so often happens with historical research, nailing down the answer to one question raises several others. In this case, who was the “fugitive black man from a rebel corps”[1] who gave the account of thousands of African American troops, organized into whole regiments, at Manassas? My colleague Dan Weinfeld, author of The Jackson County War: Reconstruction and Resistance in Post-Civil War Florida, decided to take on that question. He began by tracking down other accounts of Douglass’ speeches from this period as reproduced in Douglass’ Monthly newsletter. Sure enough, the March 1862 issue included not only the text of Douglass’ addresses, but also summaries of the remainder of the program. On February 12, one week after his speech in Boston, Douglass presented his program at Cooper Union (emphasis added):

At 8 o’clock, the [body] of the hall was nearly filled with an intelligent and respectable looking audience – The exercises commenced with a patriotic song by the Hutchinsons, which was received with great applause. The Rev. H. H. Garnett opened the meeting stating that the black man, a fugitive from Virginia, who was announced to speak would not appear, as a communication had been received yesterday from the South intimating that, for prudential reasons, it would not be proper for that person to appear, as his presence might affect the interests and safety of others in the South, both white persons and colored. He also stated that another fugitive slave, who was at the battle of Bull Run, proposed when the meeting was announced to be present, but for a similar reason he was absent; he had unwillingly fought on the side of Rebellion, but now he was, fortunately where he could raise his voice on the side of Union and universal liberty. The question which now seemed to be prominent in the nation was simply whether the services of black men shall be received in this war, and a speedy victory be accomplished. If the day should ever come when the flag of our country shall be the symbol of universal liberty, the black man should be able to look up to that glorious flag, and say that it was his flag, and his country’s flag; and if the services of the black men were wanted it would be found that they would rush into the ranks, and in a very short time sweep all the rebel party from the face of the country.[2]

Although the man who “had unwillingly fought on the side of Rebellion” is not identified, evidence strongly suggests it was John Parker, the escaped slave who had served a Confederate artillery battery at Manassas. Just a few pages after the passage above, the Douglass Monthly reprints Parker’s “A Contraband’s Story” that had appeared earlier in the Reading [Pennsylvania] Journal. As Kate Masur noted in a New York Times Disunion essay in 2011, Parker had arrived in New York at the end of January 1862, where he was interviewed again about the Battle of Bull Run and Confederate losses there.[3]

Notice in the Rochester, New York Union & Advertiser, February 12, 1862, announcing Douglass’ speech that night at Cooper Union, promising an appearance by “a rebel negro, in his regimentals, a deserter from Dixie.”[4]

Additional material published at the time strongly indicates that the man announced to appear with Douglass was, in fact, John Parker. He was speaking in the same area at the same time as Douglass. For example, on February 19, one week after the Cooper Union event, Parker was the featured speaker at a Presbyterian church across the Hudson River in Newark, New Jersey. “Parker was hired by his master to the rebels at the breaking out of the rebellion,” according to the Newark Daily Advertiser, and “has worked at Winchester, Richmond, and Manassas, and is in possession of facts and incidents which the public are invited to listen to.”[5]

Parker told his story to many people, including giving an extended interview to the New York Evening Post. Parker’s account of Manassas is vivid but badly muddled; when asked how many black persons there were “in the [Confederate] army there, he asserts that there were “one whole regiment of free colored persons, and two regiments slaves among the white regiments, one company to each.” A few paragraphs later, though, he claims that the number of black Confederate regiments at Manassas had since increased to “twelve regiments of negroes in the vicinity of Bull Run and Manassas Junction” (emphasis original). These twelve regiments, Parker again states, “are distributed one company in a regiment,” a claim that makes no sense at all.[6] A normal infantry regiment of the time consisted of ten companies of about a thousand men in aggregate; Parker’s description is profoundly unclear in terms of organization and numbers of men.

The rest of Parker’s account of First Manassas equally questionable. In his New York Evening Post interview he claimed to be “sartin” (certain) that there were 3,600 Confederate dead, and 4,000 Federals. His estimates were off by an order of magnitude; the actual numbers were around 387 and 460, respectively. He gave the number of Confederate wounded as about 5,400, which is several times the actual number.

Of course, Parker was not a trained soldier, and none of the press accounts during his speaking engagement explicitly characterize him as such. Throughout his interview with the Evening Post, Parker made it clear that while he served a Confederate gun in action, neither his sympathies nor those of his fellows lay with the Confederate cause. In his earlier interview with the Reading Journal, reproduced in the Douglass Monthly in March, Parker asserted that “we would have run over to their side but our officers would have shot us if we had made the attempt.” He claimed that “our masters tried all they could to make us fight. They promised to give us our freedom and money besides, but none of us believed them, we only fought because we had to.” To the New York Evening Post, he claimed that a slave from Alabama had been assigned by his master to serve as a sharpshooter, and in that capacity killed three Federal pickets. When he himself was killed soon after, it “was a source of general congratulation among the negroes [sic.], as they do not intend to shoot the white soldiers.”[7]

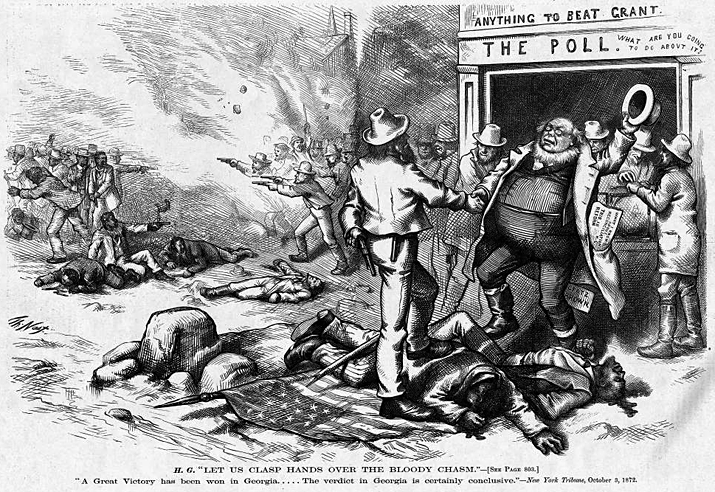

An illustration from Harper’s Weekly, May 10, 1862, showing Confederate slaves being forced to serve a cannon at gunpoint. John Parker claimed he and other slaves were put in a similar position at the Battle of First Manassas, saying that “we would have run over to [the Federals’] side but our officers would have shot us if we had made the attempt.”

Parker said that he and the other slaves manning the guns adjusted the elevating screws to fire over the heads of Union troops during the battle at Manassas. Recounting a prayer of thanksgiving given after the Confederate victory, one full of “southern braggadocio and bombast,” Parker said that “the colored people did not believe him, nor that the Lord was on that side.” Parker predicted that many slaves would continue to serve the Confederate cause, for fear that “the Lord was on the side of the South, and that they had got to be slaves always.” As for himself, Parker said, he would turn his artillery piece on Confederate forces and “could do it with pleasure,” though he dreaded the prospect of ever being in another battle again.[8]

Was Parker exaggerating his experiences for an audience that was eager to believe the worst about the Confederates? It’s certainly possible. Did Douglass, who appeared with Parker on stage and published his story in the Douglass Monthly, have doubts about the man’s account? We cannot know. But whether he was telling exaggerated stories about First Manassas or not, the best evidence of Parker’s feeling toward the Confederacy lay in the fact that he began his speaking tour soon after learning that his wife and two youngest children – a son, eight, and a daughter, six — had successfully escaped to Union lines and were now on free soil, where they were safe from any retaliation that might occur as a result of his speaking. Two older sons, seventeen and fourteen, remained in the South, the elder as an officer’s servant and the younger, sold off to another owner six months before the war. (Parker gives his owner’s name as “Colonel Thomas Griggs,” who was likely William T. Griggs [1828-83], who was a Lieutenant Colonel in the Virginia Militia but served during the war as an enlisted soldier in the Fifteenth Virginia Cavalry.) At the time of his interview Parker had been informed that his wife and two younger children had arrived in New York but had not been able to link up with them; when they were reunited, he said, he hoped they would all continue on to Canada because he was still “not quite sure of his safety here.”[9]

As Glenn Brasher points out in his 2012 volume, The Peninsula Campaign and the Necessity of Emancipation: African Americans and the Fight for Freedom, Parker’s speaking tour and that of another former slave, William Davis, gave a boost to both the cause of emancipation and for the enlistment of black soldiers in the U.S. military. (Davis also spoke at Cooper Union, on January 15, 1862, four weeks before Douglass. But Davis had come from Fortress Monroe, and did not claim to have present at First Manassas, or to have served the Confederates in any military capacity.) Thousands of people had heard Parker, Davis, or Douglass speak on the subject, and many thousands more read about it in the New York and Boston area papers. “Allegations that Southerners were coercing African Americans into combat continued to be a regular feature in the speeches and editorials of emancipationsists,” Brasher writes. “In pushing for both emancipation and the recruitment of black troops, the abolitionist newspaper Principia maintained that the Confederates ‘have been fighting in close companionship with negroes, from the beginning!’ Southern blacks, the paper claimed, ‘are regularly drilled for the service. And the proportion of negro soldiers in increasing.’”[10]

Douglass himself went on to promote Parker’s story in print, in the March 1862 issue of his newsletter, a few weeks after having made the lecture circuit in New York and Boston. Parker’s arrival in New York was fortuitous for Douglass and other abolitionists, and who pointed to Parker’s account as evidence of claims they had been making for months. Parker’s claims of vast numbers of black troops in Confederate ranks isn’t corroborated by contemporary sources, but whether they reflected a misunderstanding on his part, or an intentional exaggeration for an appreciative northern audience, matters little. The widespread belief in their existence in the first months of 1862 helped drive the national narrative that began with the appearance of the first “contrabands” at Fortress Monroe in 1861, the First Confiscation Act in August of that same year, and through the preliminary announcement of the Emancipation Proclamation in September 1862, that opened the door to enlistment of African American men in the Union army the following year. By August of 1863, Douglass would be making his case for equal pay for black soldiers to Secretary of War Stanton and to President Lincoln in person, within the walls of the White House itself.

Many thanks to Dan Weinfeld, who did the hard work of tracking down the source material for this post.

__________

[1] Boston Evening Transcript, February 6, 1862, 1.

[2] Douglass Monthly, March 1862, 623.

[3] Kate Masur, “Slavery and Freedom at Bull Run,” New York Times Disunion blog, July 27, 2011.

[4] Rochester, New York Union & Advertiser, February 12, 1862, 1.

[5] Newark Daily Advertiser, February 19, 1862, 2.

[6] New York Evening Post, January 24, 1862, 2.

[7] Douglass Monthly, March 1862, 625; New York Evening Post, January 24, 1862, 2.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Glenn David Brasher, The Peninsula Campaign and the Necessity of Emancipation: African Americans and the Fight for Freedom (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 2012), 78.; New York Times, January 16, 1862; Brasher, 78.

Decoration Day at Arlington, 1871

As many readers will know, the practice of setting aside a specific day to honor fallen soldiers sprung up spontaneously across the country, North and South, in the years following the Civil War. Over the years, “Decoration Day” events gradually coalesced around late May, particularly after 1868, when General John A. Logan, commander-in-chief of the Grand Army of the Republic, called for a day of remembrance on May 30 of that year. It was a date chosen specifically not to coincide with the anniversary of any major action of the war, to be an occasion in its own right. While Memorial Day is now observed nationwide, parallel observances throughout the South honor the Confederate dead, and still hold official or semi-official recognition by the former states of the Confederacy.

Recently while researching the life of a particular Union soldier, I came across a story from a black newspaper, the New Orleans Semi-Weekly Louisianan dated June 15, 1871. It describes an event that occurred at the then-newly-established Arlington National Cemetery. Like the U.S. Colored Troops who’d been denied a place in the grand victory parade in Washington in May 1865, the black veterans discovered that segregation and exclusion within the military continued even after death:

The black soldiers’ graves were never moved; rather, the boundaries of Arlington were gradually expanded to encompass them, in what is now known as Section 27. Most of the graves, originally marked with simple wooden boards, were subsequently marked with proper headstones, though many are listed as “unknown.” In addition to the black Union soldiers interred there, roughly 3,800 civilians, mostly freedmen, lie there as well, many under stones with the simple, but profoundly important, designation of “citizen.” The remains of Confederate prisoners buried there were removed in the early 1900s to a new plot on the western edge of the cemetery complex, where the Confederate Monument would be dedicated in 1914.

The black soldiers’ graves were never moved; rather, the boundaries of Arlington were gradually expanded to encompass them, in what is now known as Section 27. Most of the graves, originally marked with simple wooden boards, were subsequently marked with proper headstones, though many are listed as “unknown.” In addition to the black Union soldiers interred there, roughly 3,800 civilians, mostly freedmen, lie there as well, many under stones with the simple, but profoundly important, designation of “citizen.” The remains of Confederate prisoners buried there were removed in the early 1900s to a new plot on the western edge of the cemetery complex, where the Confederate Monument would be dedicated in 1914.

Unfortunately, the more things change, the more. . . well, you know. In part because that segment of the cemetery began as a burial ground for blacks, prisoners and others of lesser status, the records for Section 27 are fragmentary. Further, Section 27 has — whether by design or happenstance — suffered an alarming amount of negligence and lack of attention over the years. The Army has promised, and continues to promise, that these problems will be corrected.

As Americans, North and South, we should all expect nothing less.

____________________________________

Images of Section 27, Arlington National Cemetery, © Scott Holter, all rights reserved. Used with permission. Thanks to Coatesian commenter KewHall (no relation) for the research tip. This post originally appeared here in December 2010.

Spielberg Lays Bare the Ugly Politics of Emancipation

Smithsonian.com has a long feature by Roy Blount, Jr. on the making of Spielberg’s Lincoln, in particular the way it challenges common tropes about the 16th president. The film focuses on Lincoln’s efforts to pass the 13th Amendment in early 1865. Blount’s entire piece is worth reading, but I’m especially impressed that Spielberg and screenwriter Tony Kushner seemingly pull no punches when it comes to the pervasive, casual bigotry of 19th century Americans and the hard-nosed, carefully-crafted political maneuvering necessary to pass such a measure in 1865:

[The film] provides no golden interracial glow. The n-word crops up often enough to help establish the crudeness, acceptedness and breadth of anti-black sentiment in those days. A couple of incidental pop-ups aside, there are three African-American characters, all of them based reliably on history. One is a White House servant and another one, in a nice twist involving Stevens, comes in almost at the end. The third is Elizabeth Keckley, Mary Lincoln’s dressmaker and confidante. Before the amendment comes to a vote, after much lobbying and palm-greasing, there’s an astringent little scene in which she asks Lincoln whether he will accept her people as equals. He doesn’t know her, or her people, he replies. But since they are presumably “bare, forked animals” like everyone else, he says, he will get used to them. Lincoln was certainly acquainted with Keckley (and presumably with King Lear, whence “bare, forked animals” comes), but in the context of the times, he may have thought of black people as unknowable. At any rate the climate of opinion in 1865, even among progressive people in the North, was not such as to make racial equality an easy sell. In fact, if the public got the notion the 13th Amendment was a step toward establishing black people as social equals, or even toward giving them the vote, the measure would have been doomed. That’s where Lincoln’s scene with Thaddeus Stevens [Tommy Lee Jones, above] comes in. _____ Stevens is the only white character in the movie who expressly holds it self-evident that every man is created equal. In debate, he vituperates with relish—You fatuous nincompoop, you unnatural noise!—at foes of the amendment. But one of those, Rep. Fernando Wood of New York, thinks he has outslicked Stevens. He has pressed him to state whether he believes the amendment’s true purpose is to establish black people as just as good as whites in all respects. You can see Stevens itching to say, “Why yes, of course,” and then to snicker at the anti-amendment forces’ unrighteous outrage. But that would be playing into their hands; borderline yea-votes would be scared off. Instead he says, well, the purpose of the amendment— And looks up into the gallery, where Mrs. Lincoln sits with Mrs. Keckley. The first lady has become a fan of the amendment, but not of literal equality, nor certainly of Stevens, whom she sees as a demented radical. The purpose of the amendment, he says again, is — equality before the law. And nowhere else. Mary is delighted; Keckley stiffens and goes outside. (She may be Mary’s confidante, but that doesn’t mean Mary is hers.) Stevens looks up and sees Mary alone. Mary smiles down at him. He smiles back, thinly. No “joyous, universal evergreen” in that exchange, but it will have to do. Stevens has evidently taken Lincoln’s point about avoiding swamps. His radical allies are appalled. One asks whether he’s lost his soul; Stevens replies, mildly, that he just wants the amendment to pass. And to the accusation that there’s nothing he won’t say toward that end, he says: Seems not.

![]()

If Blount’s recounting of the film is accurate, then this movie may end up doing a tremendous service to the public’s understanding of that pivotal moment in American history. It may well do for the public’s understanding of Lincoln what Glory did, a generation ago, for recognition of the role African American soldiers played in that conflict. The popular image of Lincoln pure and unblemished saint-on-earth has always been a false and ultimately damaging one, as much as the “Marble Man” has been for Lee. Lincoln’s contemporaries didn’t see him that way. For all that Lincoln was branded as a radical abolitionist in the South, real abolitionists knew he was not one of them. According to Blount, Stevens called Lincoln “the capitulating compromiser, the dawdler,” and even Frederick Douglass, who overcame a deep mistrust of Lincoln and the Republicans in the winter of 1860-61 to become one of the president’s strongest allies and supporters, understood that Lincoln was a man who retained his own biases, yet constantly challenged himself to move beyond those. Lincoln was also a man who, regardless of his personal beliefs, had to work (like all presidents before and since) within the constraints of the political realities of the day. It was Lincoln’s willingness to work the political angle — to cajole, to flatter, to intimidate, to compromise when he had to — that allowed him to accomplish things that a firebrand like Stevens never could have, no matter how righteous his cause. As Blount says, “Stevens was a man of unmitigated principle. Lincoln got some great things done.”

There’s a saying that’s been thrown around quite a bit in the last few years, “don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good.” In other words, don’t pass up an opportunity to get most of what you want, for the sake of not being able to get everything you want. That’s good advice now, and it was undoubtedly a notion Lincoln — smart lawyer and brilliant politician that he was — would have agreed with.

When the movie hits theaters in a couple of weeks, I’m sure it will be lazily denounced in some quarters as just so much Lincoln mythologizing. A few more industrious folks will likely cite scraps of dialogue from the film to “prove” that ZOMG those Yankees were racists!. They already seem to be priming themselves to denounce it as a failure if it fails to smash every box-office record, ever. In truth, though, I think they may have a lot more to worry about with this film than the prospect of it being a big-screen affirmation of the caricatured, saintly Lincoln. If the movie is anything like Blount claims it is, it will depict Lincoln and those around him as gifted, resolute but often flawed and complex mortals who struggled and bickered and fought, and eventually accomplished great things — things like the 13th Amendment that seem so obviously right now, but were anything but assured then. If the audience takes away that understanding of the events surrounding the close of the war, it will do far more good than any exercise in hagiography might.

I can’t hardly wait.

___________

UPDATE, October 29: Over at Civil War Talk, a member asks why Frederick Douglass is not depicted in the film.

It’s a great question, and I don’t know the answer. But there’s no point in having a blog if one can’t speculate a little, so here goes:

It may be in part because Douglass was not physically present during the events depicted in the main part of the film, which focuses on passage of the 13th Amendment and the Hampton Roads Conference, which took place in January and early February 1865. I believe Douglass resided in Rochester, New York during the entire period of the war, and as nearly as I can tell, Douglass and Lincoln only met face-to-face on three occasions: in August 1863, when Douglass met with the president to urge him to equalize the pay between white and black Union soldiers; at the White House a year later, when Lincoln summoned Douglass to reaffirm his (Lincoln’s) commitment to ending slavery and to ask Douglass to use his connections to get as many enslaved persons within Union lines in the event he lost the election that fall and a new administration would end the war before decisively defeating the Confederacy; and in early March 1865, when Douglass was ushered into the president’s presence briefly at an inaugural reception to congratulate him on his reelection. This last event, though close to the time frame of the Spielberg film, was not really a substantive meeting that would have particular bearing on the story of the film.

So if my understanding of the structure of the movie is correct, there’s an easy (if not especially satisfying) explanation for his absence from the screen. What will be most interesting to see is whether Douglass’ presence is nonetheless felt in the film — if his words, his writings, his agitating — show up in the script, in allusions by other characters, in the dialogue, or elsewhere. (Elizabeth Keckley’s character [right] would be the obvious opportunity to do this, film-wise, as she admired Douglass and wrote of his being brought to meet the president in March 1865.) The real Frederick Douglass didn’t attend cabinet meetings or negotiations with representatives of the Confederate government aboard River Queen, but he nonetheless exerted a profound influence behind the scenes in both the decision to enlist black troops for the Union and in the struggle to make emancipation permanent in the closing months of the war. If Spielberg and screenwriter Tony Kushner can pull that off — making Douglass and his influence a character in the film without his actually being in the film — that will be remarkable.

So if my understanding of the structure of the movie is correct, there’s an easy (if not especially satisfying) explanation for his absence from the screen. What will be most interesting to see is whether Douglass’ presence is nonetheless felt in the film — if his words, his writings, his agitating — show up in the script, in allusions by other characters, in the dialogue, or elsewhere. (Elizabeth Keckley’s character [right] would be the obvious opportunity to do this, film-wise, as she admired Douglass and wrote of his being brought to meet the president in March 1865.) The real Frederick Douglass didn’t attend cabinet meetings or negotiations with representatives of the Confederate government aboard River Queen, but he nonetheless exerted a profound influence behind the scenes in both the decision to enlist black troops for the Union and in the struggle to make emancipation permanent in the closing months of the war. If Spielberg and screenwriter Tony Kushner can pull that off — making Douglass and his influence a character in the film without his actually being in the film — that will be remarkable.

I can’t hardly wait.

___________

Frederick Douglass and the “Negro Regiment” at First Manassas

From the Douglass Monthly, September 1861:

It is now pretty well established, that there are at the present moment many colored men in the Confederate army doing duty not only as cooks, servants and laborers, but as real soldiers, having muskets on their shoulders, and bullets in their pockets, ready to shoot down loyal troops, and do all that soldiers may to destroy the Federal Government and build up that of the traitors and rebels. There were such soldiers at Manassas, and they are probably there still. There is a Negro in the army as well as in the fence, and our Government is likely to find it out before the war comes to an end. That the Negroes are numerous in the rebel army, and do for that army its heaviest work, is beyond question. They have been the chief laborers upon those temporary defences in which the rebels have been able to mow down our men. Negroes helped to build the batteries at Charleston. They relieve their gentlemanly and military masters from the stiffening drudgery of the camp, and devote them to the nimble and dexterous use of arms. Rising above vulgar prejudice, the slaveholding rebel accepts the aid of the black man as readily as that of any other. If a bad cause can do this, why should a good cause be less wisely conducted? We insist upon it, that one black regiment in such a war as this is, without being any more brave and orderly, would be worth to the Government more than two of any other; and that, while the Government continues to refuse the aid of colored men, thus alienating them from the national cause, and giving the rebels the advantage of them, it will not deserve better fortunes than it has thus far experienced.–Men in earnest don’t fight with one hand, when they might fight with two, and a man drowning would not refuse to be saved even by a colored hand.

This quote, and most specifically the first part of it in bold above, is often waved triumphantly as an incontrovertible bit of evidence that the Confederacy did enlist African Americans as bona fide soldiers, “having muskets on their shoulders, and bullets in their pockets.” Those who advocate for the existence of large numbers of BCS seem to view Douglass’ quote as a sort of rhetorical trump card, as though the assertion of someone so genuinely revered could not possibly be questioned. If Frederick Douglass said so, the thinking seems to be, then even the most biased, politically-correct historian has to accept that.

The truth, of course, is that Frederick Douglass’ claims are subject to same scrutiny as anyone else’s. It’s worth remembering that Douglass was neither a reporter nor an historian; he was, by his own happy admission, an agitator, and is his September 1861 essay excerpted above he was again making the case for the enlistment of African American soldiers in the Union army. If there were reports that the Confederate army had used black troops at First Manassas — a battle that by September was well understood as an embarrassing setback for Union forces — then that made all the more compelling case for the Lincoln administration to respond in kind.

But why did Douglass believe that there were, or at least plausibly might be, such units in the Confederate army? He lived in upstate New York, in Rochester; he was nowhere near the battle and saw nothing of it at first hand. He might have spoken to someone who claimed first-hand knowledge of the event, but there’s no evidence that that’s the source of the claim. Indeed, the opening clause of the passage — “it is now pretty well established” — acknowledges that Douglass was not writing about something he knew to a certainty, but rather a conclusion based on what were likely numerous reports, rumors and press items.

Earlier this week Donald R. Shaffer looked at the evidence of black Confederate soldiers taking part in First Manassas, and argued that Douglass may have been basing his claim on an exchange in the Congressional Globe that took place soon after the battle, in which the involvement of African Americans in the Confederate army in a variety of capacities is discussed. Shaffer concludes, “it is apparent from the debate above that some servants and other African Americans attached to both armies were armed. This did not make them soldiers officially, but it does make murkier the line dividing soldiers and civilians attached to the armies in the Civil War.”

Dr. Shaffer, author of After the Glory: The Struggles of Black Civil War Veterans and Voices of Emancipation: Understanding Slavery, the Civil War, and Reconstruction through the U.S. Pension Bureau Files, makes a solid argument. Douglass closely followed the political debates of the day, and may well have followed the discussion in the Congressional Globe. But I would respectfully submit that it’s even more likely that he believed there were black Confederate troops at Manassas because he read it in the newspaper. From the New York Tribune, July 22, 1861, p. 5 col. 4:

A Mississippi soldier was taken prisoner by Hasbrouck of the Wisconsin Regiment. He turned out to be Brigadier Quartermaster Pryor, cousin to Roger A. Pryor. He was captured on his horse, as he by accident rode into our lines. He discovered himself by remarking to Hasbrouck, “we are getting badly cut to pieces.” What regiment do you belong to?” asked Hasbrouck. “The 19th Mississippi,” was the answer. “Then you are my prisoner,” said Hasbrouck.

From the statement of this prisoner it appears that our artillery had created great havoc among the rebels, of whom there are 30,000 to 40,000 in the field under command of Gen. Beauregard, while they have a reserve of 75,000 at the Junction.

He describes an officer most prominent in the fight, and distinguished from the rest by his white horse, as Jeff. Davis. He confirms previous reports of a regiment of negro [sic.] troops in the rebel forces, but says it is difficult to get them in proper discipline in battle array.

This account, with minor changes to the wording, appeared in newspapers all across the North, and even in Canada, in the days immediately following the battle. It was published in Batltimore, New York, Massachusetts, Albany and — yes — Rochester. A quick search of digitized newspapers suggests how far, and how often, the report of a back Confederate regiment in the field, seemingly confirmed by a captured Confederate officer, made it into print:

- St. John, New Brunswick Morning Freeman, July 25, 1861, p. 4, col. 3 (Google News)

- Baltimore American and Commercial Advertiser, July 22, 1861, p. 1 (Google News)

- Baltimore Sun, July 22, 1861, p. 2 (Google News)

- Lewiston, Maine Daily Evening Journal, p. 2, col. 2 (Google News)

- Springfield, Massachusetts Daily Republican, July 22, 1861, p. 4, col. 3 (GenealogyBank)

- Lowell Massachusetts Daily Citizen and News, July 22, 1861, p. 2 (GenealogyBank)

- Albany Evening Journal, July 22, 1861, p. 1. col. 6 (GenealogyBank)

- Jamestown, New York Journal, July 26, 1861, p. 2, col. 4 (GenealogyBank)

- Mineral Point, Wisconsin Tribune, July 26, 1861, p. 1, col 4 (NewspaperArchive)

- New York Daily Tribune, July 22, 1861, p. 5, col. 4 (Library of Congress)

- Moore’s Rural New Yorker, July 27, 1861, p. 6, col. 3 (Rochester Area Historic Newspapers)

As noted, these eleven citations are not an exhaustive list of papers that published this account in 1861; these are only examples that, 150 years later, survive in digitized, searchable form. The actual number of papers, large and small, across the country that repeated these short paragraphs may have counted in the dozens. Summaries based on Pryor’s account went even farther, with the British papers picking up and embellishing the claim. The Guardian was almost certainly rehashing Pryor’s account when it reported on August 7 that “Jefferson Davis was conspicuous on the field, on a white horse, in command of the centre of the army. A negro regiment fought on the same side.” The Illustrated London News went farther, claiming not only that such a unit went into action, but that “Northern troops found themselves opposed to a regiment of coloured men who fought with no want of zeal against them.”

I have no idea who “Brigadier Quartermaster Pryor” was; the 19th Mississippi had two Pryors, neither of which appear to be the man mentioned in the story. But who he was is less important here than assessing the reliability of his claims. I asked Harry Smeltzer of Bull Runnings for a quick assessment of Pryor’s report, as printed in the papers. Harry agreed, so long as I would indemnify him against getting dragged into the black Confederate discussion. (Done.) The Confederate numbers quoted are way off, he said, but then “numbers were wildly overstated by both sides, each being convinced they were outnumbered.” He continued:

OK – lots of [redacted barnyard term] in there, of course. The Federals did not move again on Manassas.

No 19th Mississippi at the battle: 2nd, 11th 13th, 17th, 18th. Last two were with Jones at McLean’s Ford. 2nd & 11th were with Bee and 13th with Early, so those three could have been where the 2nd Wisc was at some point. Pryor would have to have been very lost to wander from Jones to 2nd Wisc. Best bet to me is the 2nd or 11th. . . .

[Jeff Davis] arrived shortly after the fighting had stopped, during the retreat. . . .

Whoever “Brigadier Quartermaster Pryor” may have been, his claims about the battle and the Confederate army are a mess. Even allowing for the fog of war and the reality that no one, even the generals themselves, has a full and accurate picture of the fight in real time, Pryor’s claims are dubious and unreliable. It’s impossible to know, at this remove, what Pryor said on the battlefield, but what he’s quoted as saying in the newspaper is pretty worthless.

We’ll likely never know what caused Douglass to make his claim that the Confederacy had put African American soldiers on the field at Manassas. He may have heard about the battle from someone present, though Douglass’ passage doesn’t suggest that. He may well have followed the debate in the Congressional Globe, but at the same time he almost certainly was aware of the claims of “Brigadier Quartermaster Pryor,” printed in at least two papers likely to have crossed his cluttered desk in Rochester, Horace Greeley’s New York Daily Tribune and one of the local sheets, Moore’s Rural New Yorker. The presence of black men in Confederate uniform was an oft-repeated rumor that the time, and Douglass very likely saw “Brigadier Quartermaster Pryor’s” dubious account as further confirmation. Even an esteemed author like Frederick Douglass can only be a reliable as the material he has to work with.

_________________

Image: Issue of Douglass’ Monthly newspaper, via Division of Rare & Manuscript Collections, Carl A. Kroch Library, Cornell University.

The Other Speech on Decoration Day

In my last post on George Hatton, I included a newspaper account of his participation in a Decoration Day ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery. The story noted that Hatton made “a short but eloquent address” that has, apparently, been lost. Sharp-eyed readers may have also noticed that, buried in the text of the article, was a passing reference to the presence there of one Frederick Douglass. You may have heard of him.

Oddly, the newspaper makes no reference to the speech Douglass gave that day, at the memorial to the Unknown Union Dead (above), which must surely rank as one of the most compelling of its type ever offered there. It’s a short address, worth reproducing in full.

The Unknown Loyal Dead

Arlington National Cemetery, Virginia, on Decoration Day, May 30, 1871

Friends and Fellow Citizens:

Tarry here for a moment. My words shall be few and simple. The solemn rites of this hour and place call for no lengthened speech. There is, in the very air of this resting-ground of the unknown dead a silent, subtle and all-pervading eloquence, far more touching, impressive, and thrilling than living lips have ever uttered. Into the measureless depths of every loyal soul it is now whispering lessons of all that is precious, priceless, holiest, and most enduring in human existence.

Dark and sad will be the hour to this nation when it forgets to pay grateful homage to its greatest benefactors. The offering we bring to-day is due alike to the patriot soldiers dead and their noble comrades who still live; for, whether living or dead, whether in time or eternity, the loyal soldiers who imperiled all for country and freedom are one and inseparable.

Those unknown heroes whose whitened bones have been piously gathered here, and whose green graves we now strew with sweet and beautiful flowers, choice emblems alike of pure hearts and brave spirits, reached, in their glorious career that last highest point of nobleness beyond which human power cannot go. They died for their country.

No loftier tribute can be paid to the most illustrious of all the benefactors of mankind than we pay to these unrecognized soldiers when we write above their graves this shining epitaph.

When the dark and vengeful spirit of slavery, always ambitious, preferring to rule in hell than to serve in heaven, fired the Southern heart and stirred all the malign elements of discord, when our great Republic, the hope of freedom and self-government throughout the world, had reached the point of supreme peril, when the Union of these states was torn and rent asunder at the center, and the armies of a gigantic rebellion came forth with broad blades and bloody hands to destroy the very foundations of American society, the unknown braves who flung themselves into the yawning chasm, where cannon roared and bullets whistled, fought and fell. They died for their country.

We are sometimes asked, in the name of patriotism, to forget the merits of this fearful struggle, and to remember with equal admiration those who struck at the nation’s life and those who struck to save it, those who fought for slavery and those who fought for liberty and justice.

I am no minister of malice. I would not strike the fallen. I would not repel the repentant; but may my “right hand forget her cunning and my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth,” if I forget the difference between the parties to that terrible, protracted, and bloody conflict.

If we ought to forget a war which has filled our land with widows and orphans; which has made stumps of men of the very flower of our youth; which has sent them on the journey of life armless, legless, maimed and mutilated; which has piled up a debt heavier than a mountain of gold, swept uncounted thousands of men into bloody graves and planted agony at a million hearthstones — I say, if this war is to be forgotten, I ask, in the name of all things sacred, what shall men remember?

The essence and significance of our devotions here to-day are not to be found in the fact that the men whose remains fill these graves were brave in battle. If we met simply to show our sense of bravery, we should find enough on both sides to kindle admiration. In the raging storm of fire and blood, in the fierce torrent of shot and shell, of sword and bayonet, whether on foot or on horse, unflinching courage marked the rebel not less than the loyal soldier.

But we are not here to applaud manly courage, save as it has been displayed in a noble cause. We must never forget that victory to the rebellion meant death to the republic. We must never forget that the loyal soldiers who rest beneath this sod flung themselves between the nation and the nation’s destroyers. If today we have a country not boiling in an agony of blood, like France, if now we have a united country, no longer cursed by the hell-black system of human bondage, if the American name is no longer a by-word and a hissing to a mocking earth, if the star-spangled banner floats only over free American citizens in every quarter of the land, and our country has before it a long and glorious career of justice, liberty, and civilization, we are indebted to the unselfish devotion of the noble army who rest in these honored graves all around us.

The remarkable thing about this text is how well it resonates, how well it presages the ongoing arguments about how we remember the war even today, almost a century and a half after the guns fell silent. Douglass’ admonition — “we are not here to applaud manly courage, save as it has been displayed in a noble cause. We must never forget that victory to the rebellion meant death to the republic” — must necessarily ring as true today as it did then. This is what Confederate apologists do not, can not, accept: that regardless of their ancestors’ courage and sacrifice, and regardless of their individual beliefs and motivations, at the end of the day they fought for a nation founded on a terrible premise. To honor our ancestors demands that first we see them as they were, not as we’d wish they’d been.

______________________

Text of Douglass speech from Philip S. Foner and Yuval Taylor, Frederick Douglass: Selected Speeches and Writings. Image: Monument to the Unknown Dead f the Civil War, Arlington National Cemetery. Library of Congress.

Hatton Enters Politics

(This material originally appeared in January as a guest post on Ta-Nehisi Coates’ blog at The Atlantic. It originated with Coates posting a wartime letter of Hatton’s, and quickly became an exercise among followers of the blog in crowd-sourcing historical/genealogical research about Hatton himself. Special thanks goes to regular Golden Horde commenter KewHall, who found and shared critical mentions of Hatton that opened up the research on the latter parts of Hatton’s life. First installment here.)

After the war, George W. Hatton appears to have returned to Washington, D.C., where his father Henry was living. In the years after the war he married a woman named Frances. The two of them were living in Washington’s 4th Ward at the time of the 1870 U.S. Census, he employed at the Globe newspaper, and Frances (age 25) “keeping house.” As early as 1867 he was approached to serve on the D.C. council, but declined. In 1869, Hatton did serve on the “Common Council” for the District of Columbia. At the time, D.C. had three levels of governance: (1) the mayor and city department heads, (2) aldermen, and (3) the common council. This one term seems to be to only period he held public office, but he remained very active in Republican politics and was a speaker at veterans’ reunions. On Decoration Day (now Memorial Day) in 1871, he was part of a delegation of men and women who made the trek across the Potomac to the grounds of Arlington House, to hold a commemoration ceremony for the African American troops who had died during the war and were buried there on the grounds. What they found was recounted in the New Orleans Semi-Weekly Louisianan, June 15, 1871:

AT THE COLORED CEMETERY

While services were in progress at the tomb of the “Unknown” Comrade Charles Guthridge, John S. Brent, and Beverly Tucker, of Thomas R. Hawkins Post, No. 14 G.A.R., followed by Greene’s Brass Band, Colonel Perry Carson’s Pioneer Corps of the 17th District, Butler Zouaves, under the command of Charles B. Fisher, and a large number of colored persons proceeded to the cemetery on the colored soldiers to the north of the mansion, and on arriving there they found no stand erected, no orator or speaker selected, not a single flag placed on high, not even a paper flag at the head boards of these loyal but ignored dead, not even a drop of water to quench the thirst of the humble patriots after their toilsome march from the beautifully decorated grand stand above to this barren neglected spot below. At 2 ½ o’clock P.M., no flowers or other articles coming for decorative purposes, messengers were dispatched to the officers of the day for them; they in time returned with a half dozen (perhaps more) rosettes, and a basket of flower leaves. Deep was the indignation and disappointment of the people. A volley of musketry was fired over the graves by Col. Fisher’s company. An indignation meeting was improvised, Col. Fisher acting president. A short but eloquent address was made by George Hatton, who was followed by F. G. Barbadoes, who concluded his remarks by offering the following resolutions, which were unanimously adopted: