Hatton Enters Politics

(This material originally appeared in January as a guest post on Ta-Nehisi Coates’ blog at The Atlantic. It originated with Coates posting a wartime letter of Hatton’s, and quickly became an exercise among followers of the blog in crowd-sourcing historical/genealogical research about Hatton himself. Special thanks goes to regular Golden Horde commenter KewHall, who found and shared critical mentions of Hatton that opened up the research on the latter parts of Hatton’s life. First installment here.)

After the war, George W. Hatton appears to have returned to Washington, D.C., where his father Henry was living. In the years after the war he married a woman named Frances. The two of them were living in Washington’s 4th Ward at the time of the 1870 U.S. Census, he employed at the Globe newspaper, and Frances (age 25) “keeping house.” As early as 1867 he was approached to serve on the D.C. council, but declined. In 1869, Hatton did serve on the “Common Council” for the District of Columbia. At the time, D.C. had three levels of governance: (1) the mayor and city department heads, (2) aldermen, and (3) the common council. This one term seems to be to only period he held public office, but he remained very active in Republican politics and was a speaker at veterans’ reunions. On Decoration Day (now Memorial Day) in 1871, he was part of a delegation of men and women who made the trek across the Potomac to the grounds of Arlington House, to hold a commemoration ceremony for the African American troops who had died during the war and were buried there on the grounds. What they found was recounted in the New Orleans Semi-Weekly Louisianan, June 15, 1871:

AT THE COLORED CEMETERY

While services were in progress at the tomb of the “Unknown” Comrade Charles Guthridge, John S. Brent, and Beverly Tucker, of Thomas R. Hawkins Post, No. 14 G.A.R., followed by Greene’s Brass Band, Colonel Perry Carson’s Pioneer Corps of the 17th District, Butler Zouaves, under the command of Charles B. Fisher, and a large number of colored persons proceeded to the cemetery on the colored soldiers to the north of the mansion, and on arriving there they found no stand erected, no orator or speaker selected, not a single flag placed on high, not even a paper flag at the head boards of these loyal but ignored dead, not even a drop of water to quench the thirst of the humble patriots after their toilsome march from the beautifully decorated grand stand above to this barren neglected spot below. At 2 ½ o’clock P.M., no flowers or other articles coming for decorative purposes, messengers were dispatched to the officers of the day for them; they in time returned with a half dozen (perhaps more) rosettes, and a basket of flower leaves. Deep was the indignation and disappointment of the people. A volley of musketry was fired over the graves by Col. Fisher’s company. An indignation meeting was improvised, Col. Fisher acting president. A short but eloquent address was made by George Hatton, who was followed by F. G. Barbadoes, who concluded his remarks by offering the following resolutions, which were unanimously adopted:

Resolved, that the colored citizens of the District of Columbia hereby respectfully request the proper authorities to remove the remains of all loyal soldiers now interred at the north end of the Arlington cemetery, among paupers and rebels, to the main body of the grounds at the earliest possible moment.

Resolved, that the following named gentlemen are hereby created a committee to proffer our request and to take such further action in the matter as may be deemed necessary to a successful accomplishment of our wishes: Frederick Douglass, John M. Langston, Rev. Dr. Anderson, William J. Wilson, Col. Charles B. Fisher, William Wormley, Perry Carson, Dr. A. T. Augusta, F. G. Barbadoes.

If any event in the whole history of our connection with the late war embodied more features of disgraceful neglect, or exhibited more clearly the necessity of protecting ourselves from insult, than this behavior at Arlington heights, we at least acknowledge ignorance of it.

We say again that no good, but only harm can result from keeping up the recollection of the bitter strife and bloodshed between North and South, and worse still, in furnishing occasion to white Unionists of proving their hypocrisy towards the negro in the very presence of our dead.

Note that William Wormley would be the same Billy Wormley who, with George Hatton, defied the Washinton police to shoot outside the USCT recruiting office eight years previously. The black soldiers’ graves were never moved; rather, the boundaries of Arlington were gradually expanded to encompass them, in what is now known as Section 27. Most of the graves, originally marked with simple wooden boards, were subsequently marked with proper headstones, though many are listed as “unknown.” In addition to the black Union soldiers interred there, roughly 3,800 civilians, mostly freedmen, lie there as well, many under stones with the simple, but profoundly important, designation of “citizen.” The remains of Confederate prisoners buried there were removed in the early 1900s to a new plot on the western edge of the cemetery complex, where the Confederate Monument would be dedicated in 1914.

An early view of the National Cemetery at Arlington, 1867. The area north of the Arlington House where slaves, freedmen, USCTs and Confederate prisoners were buried was not maintained at the time as part of the soldiers’ cemetery, and looked far different than the neat, ordered rows shown here. Although the USCT burial ground was eventually incorporated into the National Cemetery as Section 27, it continues to be a source of dispute and controversy. Library of Congress.

Hatton got heavily involved in the 1872 presidential campaign, where he traveled in the South, primarily in North Carolina, as a “colored canvasser” on behalf of Horace Greely, the Liberal Republican candidate and publisher of the New York Tribune, a longtime supporter of the Republican Party and one of the leading anti-slavery journalists of previous years. Greeley’s “reform” platform called for an end to Reconstruction and a return of all local governance functions to the Southern states. Greeley’s campaign was supported by many Southern whites, as well, anxious to be relieved of Federal occupation. The campaign was a disaster. Greeley captured just under 44% of the popular vote against the incumbent, Grant. Greeley was in failing health both physically and mentally, however, and slipped into a rapid decline. He died just a few weeks after the election, before the electoral votes were counted.

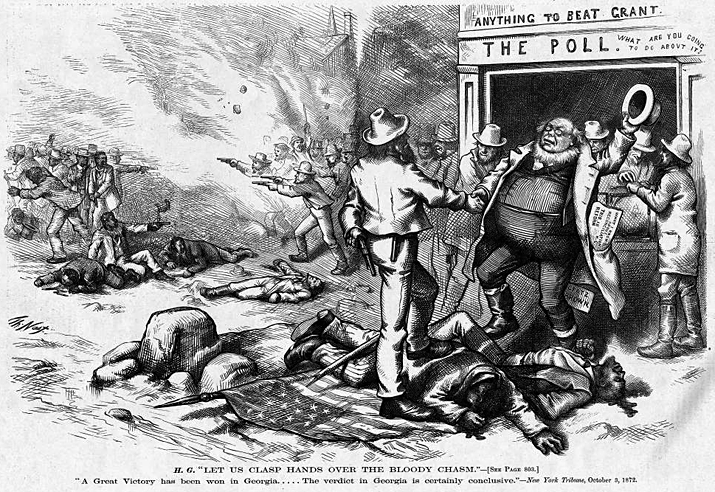

In a brutal Thomas Nast cartoon published just before the 1872 presidential election, former abolitionist editor Horace Greeley (right) steps over the bodies of murdered African Americans to shake hands with the South, represented here as a former Confederate, who is himself standing on a trampled U.S. flag and hiding a pistol behind his back. In the background, a white mob attacks freedmen who try vainly to defend themselves. HarpWeek.com.

Hatton’s work as a canvasser was both arduous and dangerous, and he became one of Greeley’s most visible campaigners. The Boston Journal, which supported Grant, noted Hatton as “one of the few colored men who support Mr. Greeley. . . [who] is described as a noisy Washington ward politician of no very high order.” But that same month, August 1872, the Times Picayune published an account by Hatton and his fellow Liberal Republican canvassers, W. M. Saunders and Walter Sorrell, of campaigning in North Carolina for Greeley that spoke to the very real dangers of campaigning:

We found on our arrival in North Carolina that the more ignorant of the colored men were massed under the control of the office-holders and the emissaries of Gen. Grant, and were laboring under the delusion that their salvation depended entirely on the re-election of Gen. Grant. There is, however, a very respectable minority of the colored people, heads of families and intelligent men of the race, who are anxious to know the past records of the respective candidates for the Presidency. Upon this class we had no difficulty making an impression. They listened to our speeches with interest, accepted our campaign documents. . . . Among the common mass of negroes [sic.], we found absolute ignorance of the past record of Mr. Greeley, Senator Sumner, or any of the lifelong friends of the race. Where there was knowledge exhibited, it was held in abeyance by the Radial leaders by means of intimidation, terrorism and assurances that Mr. Greeley’s election would effect their own re-enslavement.

The direction of the campaign by the leaders of the Grant Republicans was exceedingly unscrupulous. We were astounded and mortified to find that a number of intelligent colored men were misleading the masses. These men are actuated solely by mercenary motives, all of them being in the employment of the Administration party. . . . few of the degraded blacks, under the instigation of emissaries from Washington and the Customs-House at Baltimore, used every means to prevent the colored men from giving us a hearings, as well as to excite the people to riot. Mr. Hatton, who attended the ratification meeting at the Metropolitan Hall, Raleigh, on the evening of July 10, was immediately pointed out by the speaker as one of the “three black Ku-Klux” who had come down to mislead the people. The speaker advised the crowd after the adjournment of the meeting to wait upon them, and quietly advised them to go to their homes if they had any, and if not to attach them to the nearest tree with a rope or chain around their necks. Mr. Hatton was obliged to leave the place under the escort of the sheriff.

Metropolitan Hall, Raleigh, North Carolina, in the early 20th century. It was here on the evening of July 10, 1872 that Hatton, canvassing for the Liberal Republican presidential candidate Horace Greeley, was called out by one of the speakers as a “black Ku-Klux” and forced to leave town with a sheriff’s escort. North Carolina State Archives.

Hatton’s commitment to a presidential platform that would end Reconstruction (and the federal protections of African Americans that went with it) and return Southern states to local control is curious. But it may be hinted at in the observation that he and his fellow Greeley canvassers “found absolute ignorance of the past record of Mr. Greeley, Senator Sumner, or any of the lifelong friends of the race.” As a free man of color in a border state, one who (though young) was not only literate but eloquent in his own written prose, Hatton was likely familiar with the reputation and positions of prominent supporters of abolition like Greeley, Sumner and Douglass, and may have read their written works, as well. Hatton’s own Civil War letters (previous post) fairly rumble with the rhetoric of abolitionist oratory, and it may be that Hatton’s commitment to the 1872 campaign had less to do with Greeley’s dubious policy positions than with a longstanding admiration of Greeley himself.

To be continued. . . .

__________________

Andy: I know too little of the Reconstruction period to answer this – but isn’t it possible that Hatton assumed black electoral rights would be preserved in many of the southern states – and that returning those states to “local control” would in fact strengthen their position – given their large share of the local population – a majority, in many areas, IIRC.?

That’s entirely possible — in fact, I’d say almost certain. Given what else we know about him, through his own writings and activities before and after this period, he would not have supported a candidate or platform that he believed would undo all that he had done and worked for — indeed, nearly died for.

But it does seem that Hatton was naive about what would actually happen when local control returned to the South. Jim Crow was still in the future in 1872, but many others, particularly in the African American community, could see that their successes were very, very tenuous, and liable to be swept away under the Liberal Republican platform. Hatton himself was seen by many of them as in cahoots with white supremacists who would do just that if given the chance, and thus the angry and dangerous confrontation in Raleigh. Understand — those were black voters being urged to vigilantism against Hatton.

Very interesting Andy. The 1872 election is fascinating. Many of the original anti-slavery Republicans became Liberal Republicans, including Gratz Brown of Missouri, who was Greeley’s running mate. In fact the movement had its roots in Missouri with Carl Schurz and Brown. I think it should be noted that Greeley was also endorsed by the Democrats and that Frederick Douglass sided with Grant. It had to be a very difficult choice for him, given his friendship and appreciation for all that Charles Sumner had done for blacks. Douglass declared:

“There are many dissemblers and falsifiers of the Greeley party in the South who are seeking the control of the colored voters, by declaring to them that President Grant is not and never has been a faithful and sincere friend of my race. Indeed Senator Sumner makes a charge of this kind, and while I would not for a moment imply that I have lost faith in the honored Senator’s sincerity and integrity, still I must declare that President Grant’s course, from the time he drew his sword in defense of the old Union in the Valley of the Mississippi till he sheathed it at Appomattox, and thence to this day in his reconstruction policy and his war upon the Ku-Klux is without a deed or word to justify such an accusation.”

Douglass might even be referring to Hatton here. BTW, William Lloyd Garrison also sided with Grant.

Thanks for that. I wish I knew more about Hatton’s connection to Douglass. They were acquaintances, as witnessed by them both speaking at the Decoration Day ceremony at Arlington in 1871 (more to come on that), and certainly had friends in common, but I don’t know if it was much more than that. Although he retained an active interest in politics, after the 1872 election Hatton took on a new career and direction that removed him, physically and figuratively, from the political arena.